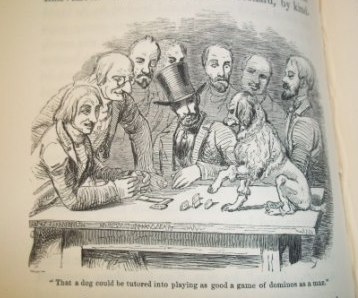

A green monkey, a baboon and…

Skeleton of Eclipse in the RCVS Museum

The story of the RCVS Museum Collection is not particularly well known – any attention it has received focussing on its most famous ‘resident’ the skeleton of Eclipse (donated in 1871 by Professor John Gamgee.) This is a shame as it housed a number of other interesting items, as a glance at the catalogue (item id 26652) compiled by Edward Reuben Edwards in December 1891 reveals.

The majority of items listed relate to horses, sheep and cattle but more exotic species are present – the first items are an ‘entire preparation of a green monkey’ and ‘the skull of a baboon’. Later on we come to the ‘skull of a polar bear’ and, my personal favourite, the ‘trachea of the first giraffe ever brought to England.’ The human animal is also represented by a ‘human eyelid’ and eight skulls amongst other things.

It appears that the care of the Museum Collection was not one of the College’s priorities. It took 27 years from the first recorded donation to the formation of the Museum Committee, in 1880. Whilst the first official record of the committee meeting is in August 1889 – nine years later.

This first meeting happened at a time when the Museum was described by Council as being in an ‘unsatisfactory state.’ There were two further meetings in the next nine months, with Council granting £100 to be spent on ‘repairs and other requisites’ and Mr Edward’s appointment at a salary of £3 3/- per week.

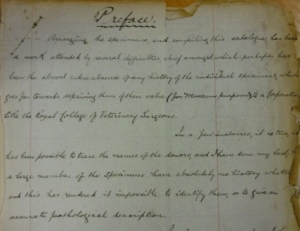

Preface of the 1891 museum catalogue

In the preface to the catalogue, Edwards’ laments that “compiling this catalogue has been a work attended by several difficulties, chief amongst which – perhaps – has been the almost entire absence of any history of the individual specimens.” In fact, he did not include any item that was unidentifiable, with the result that the catalogue only contains 334 items, whilst the RCVS annual reports for 1853-1891 record almost 500 donations. One notable absence in the catalogue is Eclipse!

Fast forward another 10 or so years and it appears that the Museum and its contents have once more fallen from the radar. On the 11 April 1902 Council member Professor Albert Mettam says:

“is the Museum Committee ornamental or is it useful. Does it ever meet, or has it anything to do with the museum? I was in the museum this morning and I think it is more a place to set potatoes in than anything else.” 1

In view of this somewhat chequered history it is little wonder that, in 1925, the RCVS gave up on its ambition to maintain a museum and agreed to disperse the specimens.

Why not check out the list of some of the more interesting donations to the museum that we have compiled from the annual reports and the catalogue?

1. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons: report of quarterly meeting of Council. Veterinary Record 19 April 1902 p654