Scabies in the horse – the first Fellowship thesis

I was recently asked the date and subject of our earliest fellowship thesis. A quick check on the catalogue showed it was written in December 1893 and titled ‘Scabies in the horse: does it demand legislation?‘

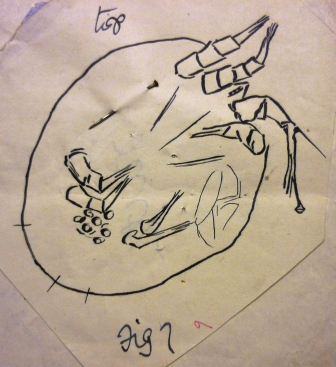

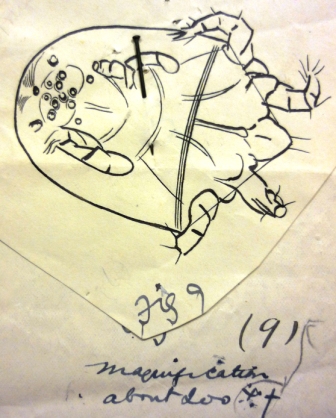

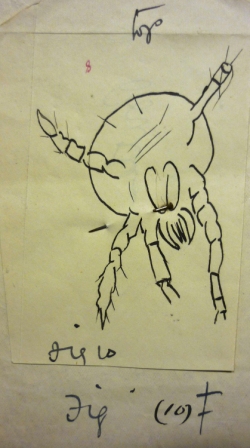

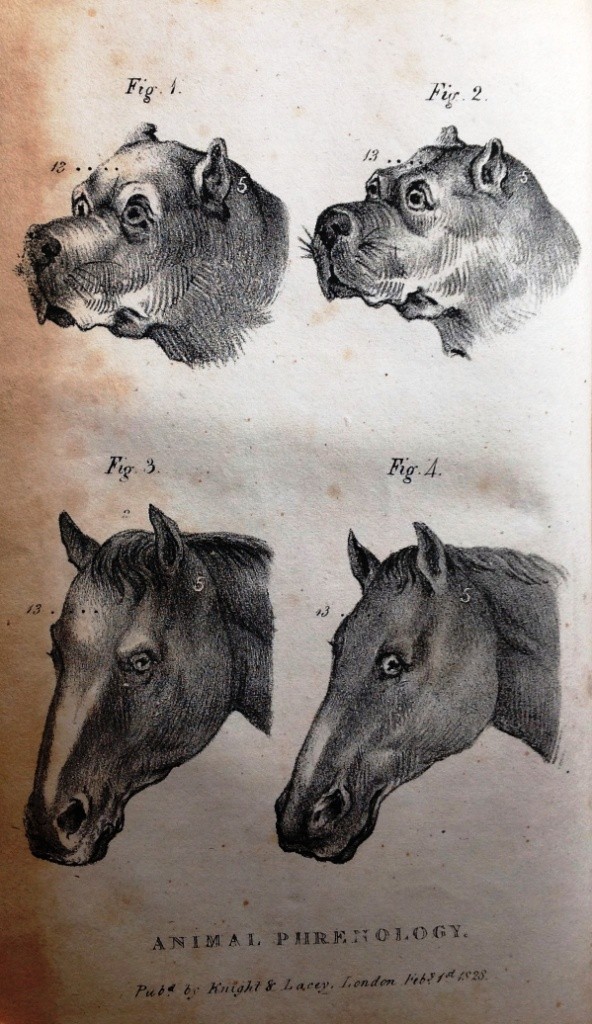

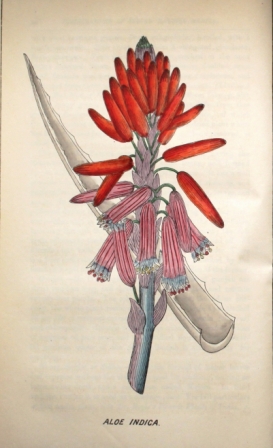

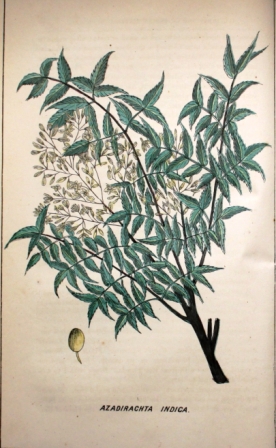

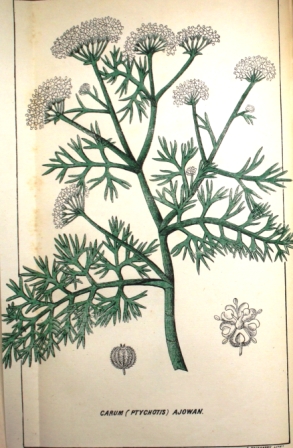

The thesis is a neatly written document  accompanied by 12 hand drawn illustrations. Regulations in place at the time stated that all fellowship submissions be ‘signed by a motto only’ – this one is signed ‘Advance’.

accompanied by 12 hand drawn illustrations. Regulations in place at the time stated that all fellowship submissions be ‘signed by a motto only’ – this one is signed ‘Advance’.

So whose motto was ‘Advance’? Well the annual report of 1893/94 reveals that the thesis had been submitted by Veterinary Lieutenant R Butler.

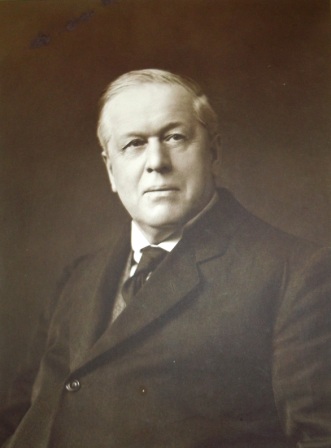

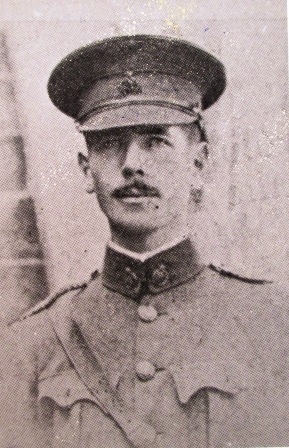

Major-General Ernest Reuben Charles Butler (1864-1959) CB CMG DSO FRCVS qualified at the London Veterinary College in 1884 and was gazetted into the Army Veterinary Department in which he served for 37 years. He spent a total of 16 years in India, was an Assistant Professor at the Army Veterinary School, Aldershot 1892-1897 and Professor from 1901-1905.

During World War One he was mentioned six times in dispatches, and made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (1915) and a Commander of the Order of the Bath (1918). In 1919 he was promoted to the rank of Major-General.

Butler also served as an examiner for the RCVS Diploma from 1895 -1904

On retiring from the army at the age of 57 he went to live in Kokstad, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa where his grave can still be seen today.

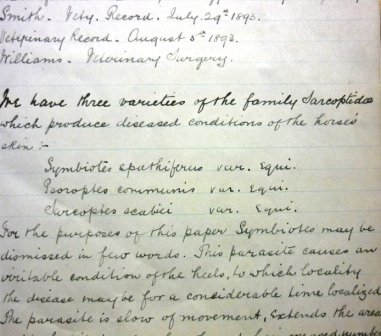

The thesis might, at just 16 pages plus bibliography, seem rather short when compared to today’s submissions; in fact it is the standard length for that time. In it Butler outlines the three varieties of Sarcoptidae which produce diseased conditions of horses’ skin, describes the history of widespread outbreaks of equine scabies and discusses means of accurate diagnosis and the fact that errors may arise from:

‘the eruption being mistaken for a non parasitic form of eczema [or from] the presence of non Psoric Acari on the skin’.

Finally he suggests possible legislative controls that could be put in place.

To aid diagnosis Butler provides illustrations of Acari (see below) drawn from materials he examined.

Filed with the thesis is a letter Butler sent in 1914 asking to borrow it from the library -a request which was granted on the proviso it was returned within a week!