The 1881 list of ‘Existing Practitioners’

In the summer, with the help of our intern Josh, we were able to sort the bundles of applications for entry on the List of Existing Practitioners which were submitted to the RCVS in 1882.

The List of Existing Practitioners came into being as a result of the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1881. The introduction to the Act talks of the need to help the public distinguish between qualified and unqualified practitioners. As part of this the Act required the RCVS to maintain and publish two documents:

- a register of its (qualified) members; and

- a list of unqualified ‘existing practitioners’ who had practised veterinary surgery for the previous five years.

The 1882/83 RCVS Annual Report states that around 1,000 applications were made for entry on the Existing Practitioner list. A committee, consisting of the President and 8 Council members (3 professors and 5 practitioners) was formed to consider the applications. At the end of their task 863 applicants were deemed eligible for the list, those rejected having right of appeal to the Privy Council.

During the summer we found 859 applications. In most cases we have three documents:

- a statutory declaration, witnessed by a magistrate or Justice of the Peace, by which the applicant declared that they had continuously practised veterinary surgery since August 27th 1876;

- a testimony as to moral character, usually given on the form supplied by the RCVS for this purpose,

- an accompanying letter which explains how the fee for inclusion on the list (£3 3s for applications made before 1st April 1882 and £6 6s after that date) would be paid.

The testimonies of moral character were supplied by a cross section of society: ‘pillars of the community’ – doctors, vicars, solicitors, councillors, magistrates etc; those who made use of the services of these unqualified practitioners – farmers, businessmen (particularly those involved in the transportation of goods using horses) etc, and of course members of the RCVS.

In a few cases we have more documents. For example John Oddy of Cleckheaton sent a 1m long document containing 35 names who would testify he was of ‘good moral character and integrity’. Whilst Edward Allcock of Dublin supplied a copy of his indenture of apprenticeship, dated August 1835, to Joseph Bretherton MRCVS.

In most cases though the additional documents are because the validity of the application has been called into question – they are ‘letters of protest’.

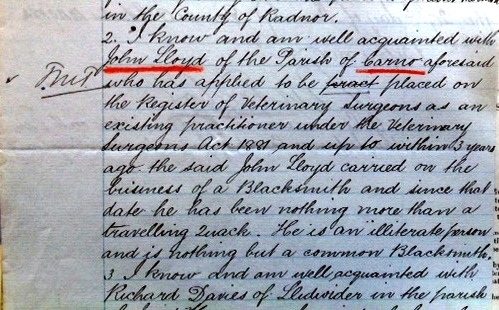

These ‘protests’ are nearly all from MRCVS, and they reveal something of the tension that existed between some qualified and unqualified practitioners. For example an MRCVS writes that John Lloyd of Montgomeryshire was “up to within 3 years ago … a Blacksmith and since that date he has been nothing more than a travelling quack. He is an illiterate person … a common blacksmith”. In spite of this Lloyd’s application was successful.

We only found two applications that are clearly marked as having been rejected at the first stage.

One is from Edward Drew of Oldham. From the documents we can see that his application was initially rejected because he hadn’t practised veterinary surgery continuously for the previous 5 years. Drew persuaded the Committee to reconsider his application explaining that he had been forced to give up his practice and take up other employment due to “being connected with another business … by which I lost a considerable sum of money”. He also sends a document containing 27 names in support – top of the list was Thomas Greaves FRCVS, former RCVS President and current Council member – which can’t have done any harm as his application was eventually successful.

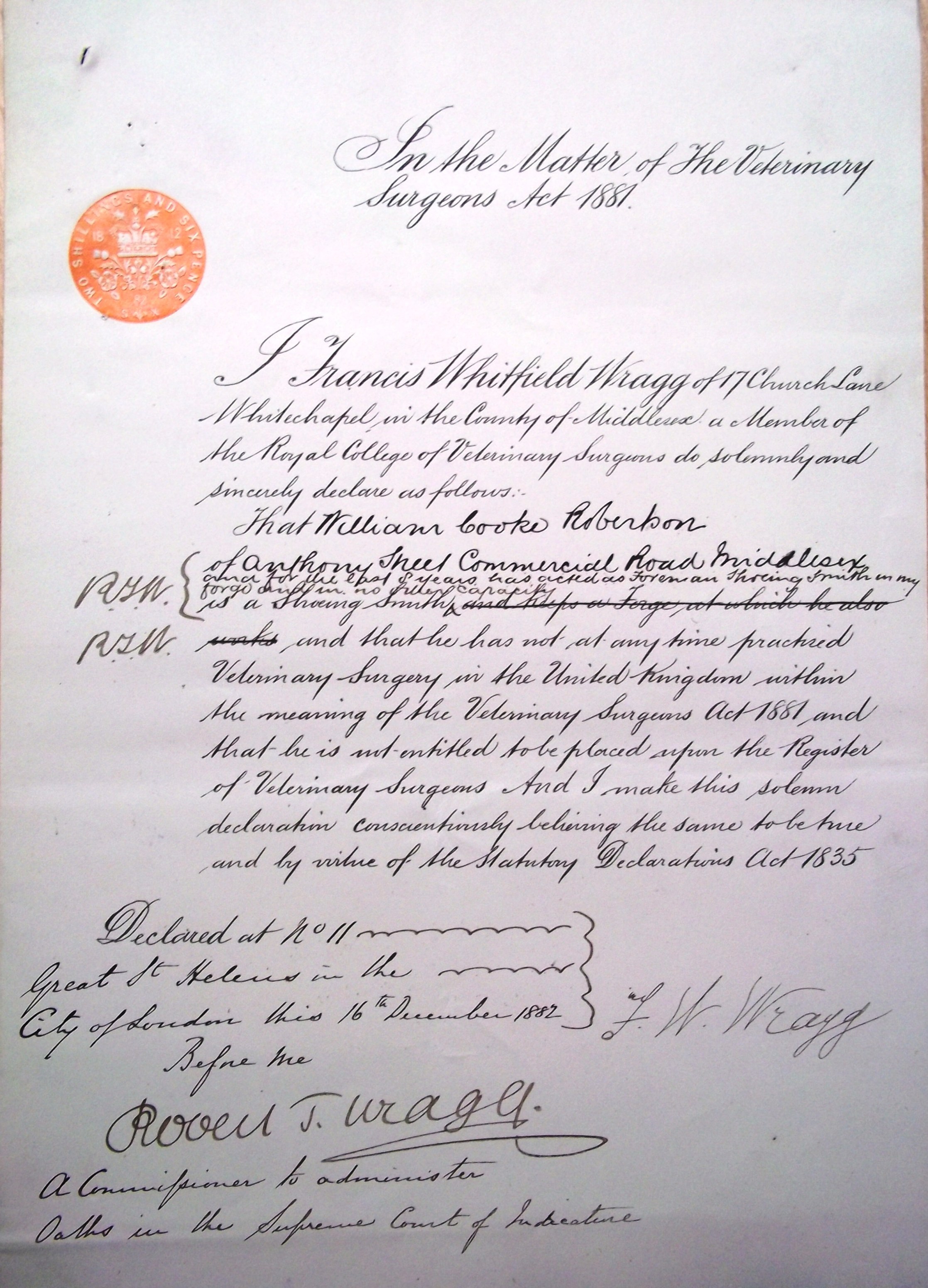

The other rejected application is from William Robertson of Commercial Road, London. Those appealing against his application included Francis Whitfield Wragg, who was serving on Council and the Committee considering the applications at the time. (I wonder if he declared a conflict of interest?) It seems that Robertson had worked in Wragg’s forge in Whitechapel as – in Wragg’s words – a ‘foreman shoeing smith’. There are 9 other ‘protests’ all but one of them from people related to Wragg’s practice.

Documents show that Robertson took his appeal to the Privy Council where it was dismissed – alongside an appeal by Stephen Pettifer, whose application we have not found.

The Annual Report concludes it section on the listing of Existing Practitioners thus:

‘the labours of the Committee in accomplishing their task of selection have been extremely onerous and full of anxiety … At no time in the history of the Royal College has a Committee had imposed on it such a heavy and anxious task … with the conclusion of this registration the most embarrassing portion of the responsibility thrown upon the Royal College by the Act has been disposed of.’