Rabbits: from prey to pet

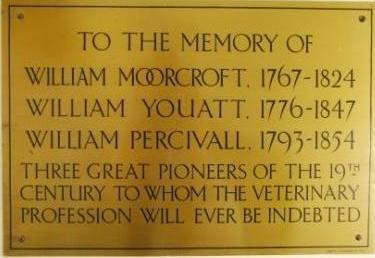

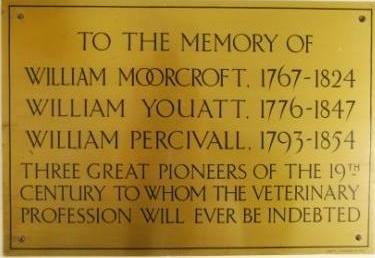

Even though the domestication of the rabbit occurred 2000 years ago, rabbit care before the 19th century was not in the local vet or farmer’s repertoire. This explains the lack of lagomorph related content in our historical collection.

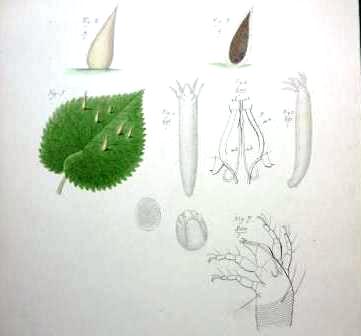

Contrary to what you may think, rabbits don’t belong to the rodent order but sit in a separate group called lagomorpha. Lagomorphs have four incisors in the upper jaw and are entirely herbivorous – unlike their similar-looking cousins, the rodents.

We can thank central European monks for the full domestication of the wild European rabbit. Within the monastery walls rabbits would freely roam and eventually became tame. In 600 AD, Pope Gregory the Great declared that unborn or new born rabbits were no longer considered meat. Strangely enough they were to be thought of as aquatic creatures. Conveniently, this meant they could be eaten during Lent and so the practice of rabbit keeping steadily increased in monasteries.

One of the few books in our historical collection about rabbit keeping has the rather wordy title A practical treatise on breeding, rearing and fattening all kinds of domestic poultry, pigeons and rabbits; also the management of swine, milch cows and bee; with instructions for the private brewery on cider, perry and British wine making by Bonington Moubray (1834). In this book, the subject of rabbit rearing is lumped together with all the activities that could take place on a small holding, so that a countryman could have one volume for all his needs. The book contains tips on cooking rabbits (“they make a good dish, cooked like a hare”), extols the quality of the skin and fur (the author is “in the habit of drying the skins, for the linings of nightgowns”) and mentions the four types of rabbits (warreners, parkers, hedgehogs and sweethearts, in case you were wondering).

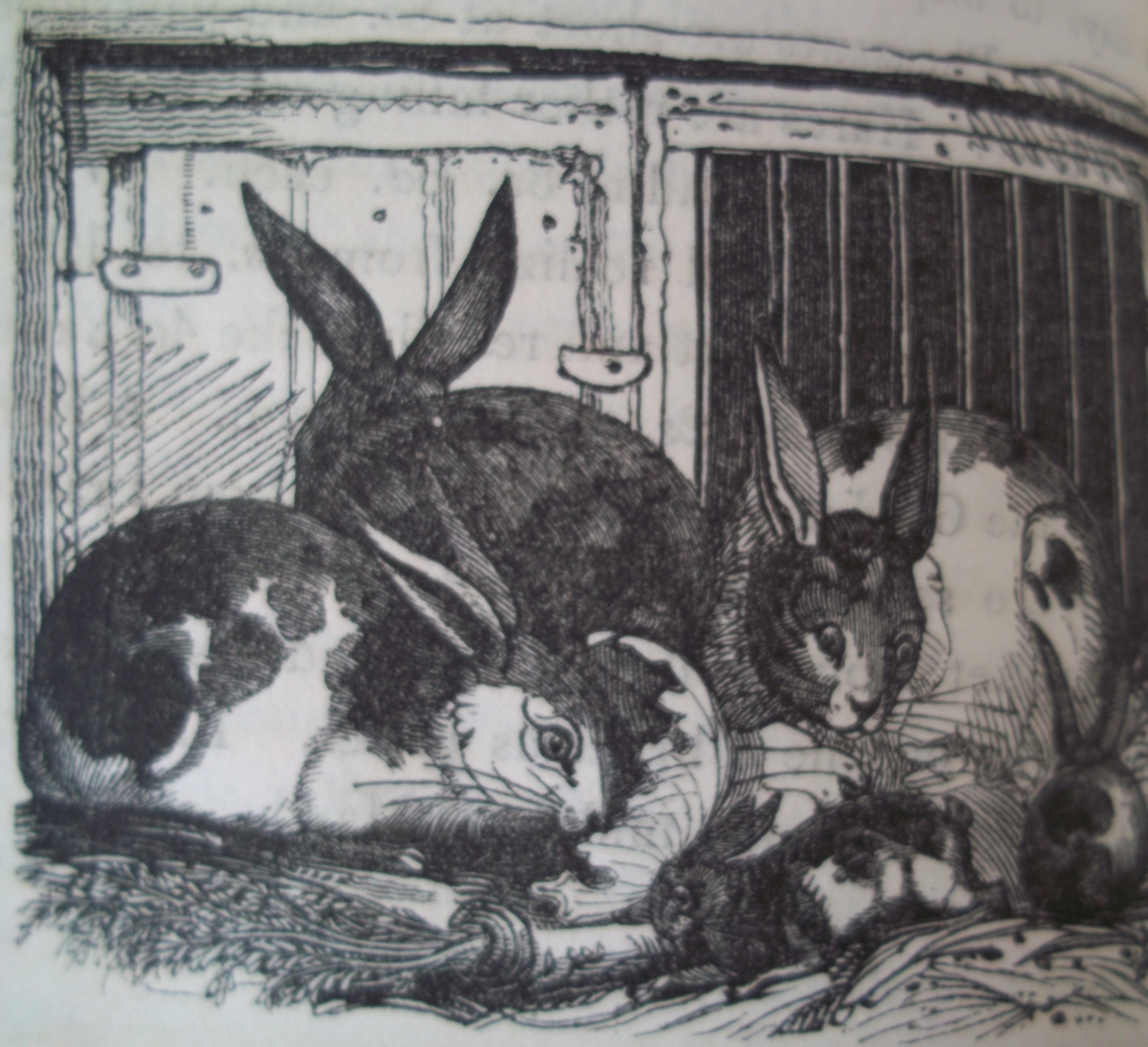

By 1840, the Metropolitan Rabbit Fancy Club was established in England, were members showed only one breed, the ‘lop eared’. As animal fancying swept Europe in the late 19th century, rabbits were still killed for their meat but were increasingly kept as parlour pets and exhibited at shows.

Rabbit care has changed a lot over the centuries but one thing still rings true “the teeth of rabbits are very effectual implements of destruction to anything not hard enough to resist them” (Moubray, 1834). Those lagomorphs can bite!