“Sore backs appear inseparable from mounted service, they have existed as long as the horse has been used in war … it was reasonable to suppose … as knowledge advanced, a reduction in this class of injury should have been possible.”

So says Frederick Smith in his book A veterinary history of the war in South Africa 1899-1902 (item id 003722) in the section on the history of sore backs. He then goes on to claim that in the 40 years following the Battle of Waterloo all “the lessons of war appear to have been forgotten.”

Later campaigns meant that the topic became a matter for discussion again. In the early 1880s General Sir Frederick FitzWygram, Commander of the Cavalry Brigade, studied the problem showing that it was often the construction of the saddle that was to blame.

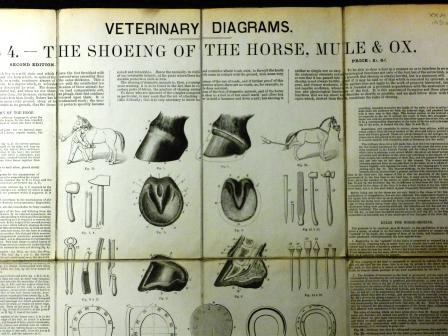

Smith’s Skeleton of horse showing back bone and ribs

The topic then became the subject of a series of lectures, delivered by Smith, at the Army Veterinary School in Aldershot. These lectures were eventually published in 1891 as A manual of saddles and sore backs (item id 26542).

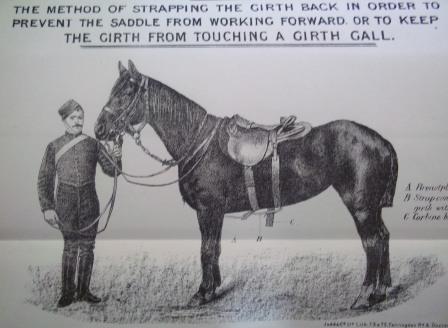

The manual is set out in four sections: the first covers the anatomy and physiology of the back because, as Smith states, “no accurate conception of the fitting of a saddle … can be formed until we have some knowledge of the structure on which the saddle rests.” This is followed by 16 pages on the construction of a saddle, 8 pages of instruction on how to fit one properly and finally 17 pages on ‘sore backs – how they are caused, prevented and remedied.’ The book contains 11 illustrations – 6 are anatomical, 5 on fitting a saddle with the final one showing the sites of the various injuries.

In spite of the lectures and manual it would appear that little changed – when referring to the South African War Smith states that “sore backs represented one of the chief causes of inefficiency.”

Smith – How to fit a girth correctly

This view is also expressed by William Snowball Mulvey in his little (20 page) book Sore back and its causes in army horses on a campaign (item id 26379) which was published in 1902. Sore backs had been the topic of Mulvey’s RCVS Fellowship Thesis and one of the reasons for this choice was “The fact that nine out of every ten cases which came before my notice in South Africa were the so-called sore backs.” By publishing his thesis Mulvey hoped to make his observations more widely available.

The book is very much a practical manual – it identifies 9 causes of sore backs and then shows how to prevent the injuries occurring in the first place – as Mulvey says in his closing words “the rational treatment of sore backs, is of course, the removal of the cause.”

Interested in finding out more? The notes and illustrations Smith made when carrying out research for his lectures and manual form part of the Frederick Smith Collection , they provide a fascinating insight into the meticulous way Smith carried out his rearch on this topic.

References

Mulvey, William Snowball (1902) Sore back and its causes in army horses on a campaign . Fellowship theses later published by H & W Brown

Smith, Fred (1891) A manual of saddles and sore backs London: HMSO

Smith, Frederick (1919) A veterinary history of the war in South Africa 1899-1902 London: H. & W. Brown

lague).

lague).